Okay, the above title is a half truth. It’s a sort of favorite spinning fiber and it’s supposed to be called bamboo….. rayon. Eek! Why? Because rayon is a regenerated cellulose process, and in the case of bamboo rayon, bamboo stalks are the cellulose fiber.

Bamboo comes in two spinning fiber forms, one is transformed chemically into a spinning fiber, the other mechanically. Bamboo rayon which I’ll talk about now is the chemically transformed one, and bast bamboo, which I will talk about in a later post, is the mechanically transformed one.

I have a love, maybe love, I really don’t love this fiber type of relationship.

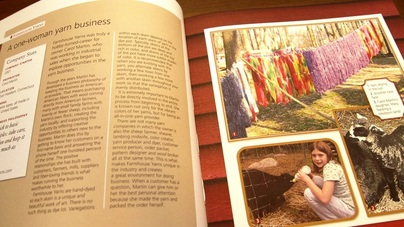

Things I love: It’s incredibly soft and has a beautiful luster. Look at the pictures below, the shine is just gorgeous. It also dyes relatively easily (I use Dharma Trading dye for plant fibers) and, I’ll say it again, beautifully. Yes, bamboo is a renewable resource. I grew up where there were lots of bamboo groves, and it grows and grows and grows. It’s soft on the hands to spin. The resulting yarn has a wonderful drape and great stitch definition if knitted.

Things I don’t: It’s very fine and gets on clothes, furniture, the carpet, while spinning. I find it staticy so when I’m pulling the roving into thinner slivers to spin I have the static halo, which has fibers sticking to everything close to it, like my hands. It’s made by a chemical process where the bamboo is dissolved into a slurry with chemicals and fed through a machine that makes the fibers. The grass is natural, the fiber is manmade, which is why the correct classification is bamboo rayon. It’s obviously not the only fiber like this- tencel can also be called wood rayon, because it’s made from trees in a similar process. ( I will talk about tencel in a later post. ) Drafting take some getting used to because the fiber can be at the same time slippery and clingy- all that shine equals slip, but the very fine fibers don’t want to draft (i.e. pull apart) sometimes. I find it easier to either spin in small slivers of roving about ¼ inch wide, or predraft the roving if I’ve only slivered into widths of ½ inch. Now, once I’ve spun about 100 yards, I still hate the staticy fiber that gets everywhere but I stand up and look at my bobbin and admire the lovely yarn and keep spinning. When I’m done I get out the sticky roller and clean up all the errant fibers.

Bamboo comes in two spinning fiber forms, one is transformed chemically into a spinning fiber, the other mechanically. Bamboo rayon which I’ll talk about now is the chemically transformed one, and bast bamboo, which I will talk about in a later post, is the mechanically transformed one.

I have a love, maybe love, I really don’t love this fiber type of relationship.

Things I love: It’s incredibly soft and has a beautiful luster. Look at the pictures below, the shine is just gorgeous. It also dyes relatively easily (I use Dharma Trading dye for plant fibers) and, I’ll say it again, beautifully. Yes, bamboo is a renewable resource. I grew up where there were lots of bamboo groves, and it grows and grows and grows. It’s soft on the hands to spin. The resulting yarn has a wonderful drape and great stitch definition if knitted.

Things I don’t: It’s very fine and gets on clothes, furniture, the carpet, while spinning. I find it staticy so when I’m pulling the roving into thinner slivers to spin I have the static halo, which has fibers sticking to everything close to it, like my hands. It’s made by a chemical process where the bamboo is dissolved into a slurry with chemicals and fed through a machine that makes the fibers. The grass is natural, the fiber is manmade, which is why the correct classification is bamboo rayon. It’s obviously not the only fiber like this- tencel can also be called wood rayon, because it’s made from trees in a similar process. ( I will talk about tencel in a later post. ) Drafting take some getting used to because the fiber can be at the same time slippery and clingy- all that shine equals slip, but the very fine fibers don’t want to draft (i.e. pull apart) sometimes. I find it easier to either spin in small slivers of roving about ¼ inch wide, or predraft the roving if I’ve only slivered into widths of ½ inch. Now, once I’ve spun about 100 yards, I still hate the staticy fiber that gets everywhere but I stand up and look at my bobbin and admire the lovely yarn and keep spinning. When I’m done I get out the sticky roller and clean up all the errant fibers.

Things in the middle: It’s a silk alternative, meant to be readily available and cheaper than silk. I’ve seen it been called bamboo silk, which, okay, it’similar to the luster and feel of silk (spun that too, will write about at some point), but it’s not silk. Silk is a natural fiber from moths, this is a chemically processed grass, a beautiful one, but not completely natural as it’s been endlessly touted.

Don’t get me wrong, I still like bamboo rayon but I have issue with the chemicals used in the process. Most, if not all of it, is made in China, and I have read their process is getting more environmentally friendly. I don’t want to say I won’t spin it every again because I still love the results.

Bast bamboo fiber review coming at a later time.

Below is, as usual, some of my handdyed and handspun bamboo rayon yarns.

Don’t get me wrong, I still like bamboo rayon but I have issue with the chemicals used in the process. Most, if not all of it, is made in China, and I have read their process is getting more environmentally friendly. I don’t want to say I won’t spin it every again because I still love the results.

Bast bamboo fiber review coming at a later time.

Below is, as usual, some of my handdyed and handspun bamboo rayon yarns.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed