|

It's a gloomy trying to rain day in Wyoming and I've been dyeing Lincoln wool and a superwash Columbia Rambouillet wool roving. I've been doing this for years and the process is pretty automatic to me. Clean wool, stuff in canning jars, make dye, add dye, heat set, let cool, dry, spin. Today I looked at the curly Lincoln wool and squished roviing in the jars and noticed something- the play of color and texture is actually very intriguing. So much, that I took the pictures you see below. Maybe I should pay attention more often.  Welcome back! Well, at least to me. I’ve been slacking. Okay, that’s not completely true. I have been spinning lots of yarn, dyeing lots of wool, and knitting a sweater (the Terra Linda Cardigan if you’re interested.) Last month I also was gifted a spinning wheel, my third one. She’s an Ashford Traditional, first purchased by the original owner in 1976. She was originally dark walnut, but I painted her teal and she’s used for demonstrations sometimes. Her color, incidentally for those who are fans of Daryl’s Restoration Over Hall on DIY network, is the same as the reproduction historic sink in the new kitchen. She’s supposed to represent something from the 1800s and I spend a lot of time explaining that the color is, yes, historically correct. It's a bit darker than pictured. I also spend a lot of time explaining the theory of spinning yarn- the how to's and different types of wool. One family found out I can ramble if you let me. Her name is Charlotte. If you’re wondering, and if you’re not, the dark walnut bench behind it was something that I built from a kitchen cabinet I got from Menards. I needed something to #1- store wool, and #2, be the right height to sit and spin. I find around 17 inches tall is the right height for me. At some point I will give a thorough review. And at some point I will give a history lesson on historic painted spinning wheels. Actually, I’ll do that right now. I’ve been researching spinning wheels lately- forms, styles, and colors. While a vast majority of wheels are natural wood colors, I have found two colors that predominate when they are painted- shades of medium-dark blues and greens. I found one with burgundy trim. Since I can ramble on about anything spinning related I will stop now. See you soon!  I have 2 spinning wheels (right now). My first one was a Louet S17 single treadle which I wrote about previously. My new wheel, received last August, is an Ashford Kiwi 2. I got the unfinished one so I could paint it myself. Ashford changed some features from the original Kiwi, which I did consider 10 years ago. There is a sliding hook on the flyer which I thought I wouldn’t like but I was wrong. We’ll see if they last 10 years though because they are just wire. The new bobbins are bigger for the sliding hook flyer. I can get a good amount of yarn on them- I’ve got 298 yards of DK weight on one. I was having trouble with the fuzziness of the fluffed locks for my fleecespun art yarns getting caught on the cup hooks at the top of the flyer, so I bent one in to close it. It helps, but it still gets caught once in awhile. The fix is easy and I can fix while the wheel is in motion. Just pull the yarn back towards you and let go to wind onto the bobbin- it has worked every time. The wheel design is also new and I think much prettier than the original. The Kiwi is a Scotch tension wheel, also known as flyer lead. The poly drive band goes around a whorl that attaches to the flyer, there is a clear wire and spring that goes around the bobbin that controls the uptake of yarn on the bobbin. It comes standard with 2 ratios: 5.5 and 7.25. I have used the 5.5 to test it but like the Louet, spin mostly on the 7.25. There is a high speed adapter kit and a jumbo flyer kit available to expand ratios available. I hope to get the jumbo flyer kit for the bigger 8 ounce bobbins, but would also like to get the high speed kit since I spin a lot of sock yarn on this wheel. The higher speed ratio means more turns of the flyer, which means I don't have to wildly treadle to get it fast- the whorl will do it for me.  Treadling is very, very smooth and pretty quiet. When it’s not quiet it needs a little oiling as per Ashford's instructions that came with the wheel. I use sewing machine oil I got from Joanns Fabrics. I love the double treadles. I like that I’m using both feet, not just one as on the Louet. Due to a previous accident about three years ago, using both also is just a better idea for me so not to stress out my right foot and leg. As mentioned above, I got the unfinished version. Out of the box the wood is smooth to the touch, the edges are sanded of sharpness. I painted mine in the colors Jungle Green and Blackberry Harvest from Home Depot. The wheel also has a yellow stamped botanical butterfly design on it. It comes flat packed and requires assembly. It has a pegged, hex bolt, and screw construction and once assembled is very sturdy. The base has a square design which adds to its sturdy feel- I never feel this will tip over, even when spinning on carpet. If you get one, have a cordless drill handy because the holes can be tight to screw into. For the beginning of the build all we had was a screwdriver, until we got tired and went and found the cordless. Also have a rubber mallet handy to bang in the pegged joints. I love this wheel. I love the double treadles and the way they just work so well, free, and easy. I love the feel of the wood to the point I want to buy another one just to stain it mahogany (I probably won't, and Ashford Travellers is next on the wish list). It is considered a “beginners” wheel but I would recommend to anyone looking for a double treadle on the lower end of the price scale. It has accessories which add to it's spinning ratios, and the adapters are not expensive so it is versatile. I’ve taken it on a few camping trips and it’s small enough to easily sit on the floor of my friend’s truck. I think because of the quality of build and finish from Ashford it will be durable for the long haul.

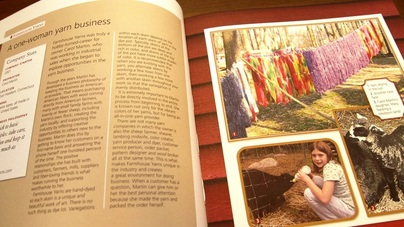

Okay, the above title is a half truth. It’s a sort of favorite spinning fiber and it’s supposed to be called bamboo….. rayon. Eek! Why? Because rayon is a regenerated cellulose process, and in the case of bamboo rayon, bamboo stalks are the cellulose fiber. Bamboo comes in two spinning fiber forms, one is transformed chemically into a spinning fiber, the other mechanically. Bamboo rayon which I’ll talk about now is the chemically transformed one, and bast bamboo, which I will talk about in a later post, is the mechanically transformed one. I have a love, maybe love, I really don’t love this fiber type of relationship. Things I love: It’s incredibly soft and has a beautiful luster. Look at the pictures below, the shine is just gorgeous. It also dyes relatively easily (I use Dharma Trading dye for plant fibers) and, I’ll say it again, beautifully. Yes, bamboo is a renewable resource. I grew up where there were lots of bamboo groves, and it grows and grows and grows. It’s soft on the hands to spin. The resulting yarn has a wonderful drape and great stitch definition if knitted. Things I don’t: It’s very fine and gets on clothes, furniture, the carpet, while spinning. I find it staticy so when I’m pulling the roving into thinner slivers to spin I have the static halo, which has fibers sticking to everything close to it, like my hands. It’s made by a chemical process where the bamboo is dissolved into a slurry with chemicals and fed through a machine that makes the fibers. The grass is natural, the fiber is manmade, which is why the correct classification is bamboo rayon. It’s obviously not the only fiber like this- tencel can also be called wood rayon, because it’s made from trees in a similar process. ( I will talk about tencel in a later post. ) Drafting take some getting used to because the fiber can be at the same time slippery and clingy- all that shine equals slip, but the very fine fibers don’t want to draft (i.e. pull apart) sometimes. I find it easier to either spin in small slivers of roving about ¼ inch wide, or predraft the roving if I’ve only slivered into widths of ½ inch. Now, once I’ve spun about 100 yards, I still hate the staticy fiber that gets everywhere but I stand up and look at my bobbin and admire the lovely yarn and keep spinning. When I’m done I get out the sticky roller and clean up all the errant fibers.  Things in the middle: It’s a silk alternative, meant to be readily available and cheaper than silk. I’ve seen it been called bamboo silk, which, okay, it’similar to the luster and feel of silk (spun that too, will write about at some point), but it’s not silk. Silk is a natural fiber from moths, this is a chemically processed grass, a beautiful one, but not completely natural as it’s been endlessly touted. Don’t get me wrong, I still like bamboo rayon but I have issue with the chemicals used in the process. Most, if not all of it, is made in China, and I have read their process is getting more environmentally friendly. I don’t want to say I won’t spin it every again because I still love the results. Bast bamboo fiber review coming at a later time. Below is, as usual, some of my handdyed and handspun bamboo rayon yarns.  We need to start here, specifically how a Spaniard sheep got to New Mexico: Navajo churro sheep are descendants of the Iberian Churra sheep, brought to the Rio Grande Valley (i.e. New Mexico) in 1598 as Spain was establishing villages in this new area (at least to them). The initial number brought with Don Juan Onate and his settlers was 2900 sheep. The Spanish enslaved the Pueblo people and had them work as shepherds and weavers, the Navajo acquired sheep through trade and raiding. In 1680, the Pueblo people revolted and threw out the Spanish, but they didn’t take their sheep. The Navajo acquired more sheep and expanded the flocks for food, but more importantly for this story, for their wool. These sheep remained in isolated flocks throughout the area that would become New Mexico and Arizona with the Navajo and Pueblo peoples. In an attempt to get Navajo lands for Western settlers, the US government ordered the destruction of Navajo orchards, but also their sheep. This military action culminated with the Navajo Long Walk, where they were forced to march 300 miles to Bosque Redondo, New Mexico. As with the Cherokee Trail of Tears, many didn’t make it. After 3 years, the Navajo were allowed to return to their ancestral land and families were issued “native sheep” from flocks that were from New Mexican villages. The last hurdle the sheep and the Navajo had to endure was a 1930s program to eradicate some of the livestock on the Navajo reservation due to a severe drought. By this time the flock which had grown to over ½ million was reduced by about 30%. The Navajo said they knew how to manage their stock of sheep, goats, and horses on their land as they had for hundreds of years and this was unnecessary. By the 1970s, the Navajo Churro was critically endangered at around 500 head. Several conservancies stepped in and slowly the sheep breed has been revitalized, although still in low numbers compared to many other sheep breeds, but it is no longer facing extinction. Churro sheep are double coated, with a long straight coarse top coat and a softer, shorter inner coat. The staple length is 6-12 inches for the outer coat, and 3-5 for the inner coat. Many have horns, some with four or more. They are well suited to the harsh environment of the desert Southwest of cold night, hot days, and little water. They come is all colors of brown, black, white, and pretty much any color in between. It’s supposed to be a no- luster wool but I have seen a few fleeces with a pearlescent sheen to them. I’ve got my hands on several fleeces and mini mill produced roving over the past years. All but one have been from New Mexico, the stray one was from a farm in Montana. Most have been dark brown, grays, and black. I’ve also spun some oatmeal color roving before. I also have one gorgeous white fleece I’m hanging onto for a spinning/natural dyeing project. I’ve got fleeces with really coarse outercoats and some where the outercoat was almost as fine as the innercoat. I don’t separate the coats, I just fluff and spin, however I’ve found that is the outercoat is really coarse it is actually easier to separate the two. You hold each end of the fleece and pull apart. In general, Navajo churro is not next to skin soft. Lamb fleeces are the exception. However, you need to remember the breed’s wool was used for weaving hardwearing objects such as saddle blankets and rugs, which the wool’s coarseness is perfectly suited for. Below is some of my Navajo churro handspun yarns. All but one are natural colored.  I did a bit of spinning last weekend, about 800 yards total, mostly on my Louet S17. I guess there’s something about Spring in the air because my yarn had flowers growing from it! Okay, not really growing from it, but they are spun into it. I call this Flowered Fleecespun, because it has flowers and is spun from hand dyed wool locks. I seem to spin this series in cycles because I was looking back at my yarn archive and I seem to, fittingly, spin this during the warmer months. I don't have much of a yard for a garden, or much gardening skills for that matter, but my yarn can bloom. New flowered fleecespuns (the ones pictured at right) will be available in my Etsy shop soon. Below are some of my flowered handspun yarns from the past two years. I was spinning some handdyed Wensleydale wool roving last night. Below is some pics of the yarn in progress. It is a self-striping yarn. The roving had blocks of color so instead of slivering the wool, I pulled out chunks by color. It's turned out to be a very bright colored and fun yarn! That's my Ashford Kiwi 2 spinning wheel that I'm using.  So when you hear the word Shetland do you think of small ponies and dogs that look like mini-Collies? Windswept islands? Lace? I think of lace first (because I love knitting lace) and then I think of sheep. Like the miniaturized version of horses and dogs that inhabit the Shetland Islands, the sheep are also smaller too, topping out at 125 pounds. For comparison, my friend’s St. Bernard dog weighs more at 140 pounds. The breed is old, and retains many other historical characteristics besides size, most notably color. Where many sheep breeds have been bred to be large flocks of white to be sold to the textile industry, Shetland sheep still come in a rainbow of earthy colors- from creams, browns, grays, blacks, and all color in-between. Traditional names like emsket, shaela, mioget, and moorit are still regularly used. Shetland sheep came in single or double coat, or a wavy coat. It is soft. Staple length of the fleeces I have spun have ranged from 3-7 inches long. Below is some pictures of fleeces I have worked with throughout the years and I never have got a coarse fleece. I’ve also worked with all three types- I don’t prefer one over another. I don’t separate the double coat fleece, I just combine the two either just by fluffing by hand or carding, and spin. You can also get Shetland roving in several colors from a variety of sellers such as the Woolery, Paradise Fibers, and Bountiful Spin and Weave. Roving is prepared fibers. It is combed into a ropelike.. well.. rope and ready to spin. I find it easier to spin if I separate the rope into several strips, about ½ inch wide. The roving comes in brown, gray, and white. I love spinning Shetland wool, hence the “Favorite Fibers” title. I love the range of colors and it is always reliably soft. I mentioned above where I get roving. I have got fleeces from sellers on Ebay and Etsy. There are also farms whose info is in the classifieds section of Spin Off Magazine. I have an oatmeal Shetland fleece that I am washing right now and will be spinning soon, so update to come! Below is a sampling of the Shetland handspun yarns I have created through the years.  Insert wonderful intro paragraph… Okay I can’t think of one. Let’s start it like this: I love this book and I hope to be like many of these companies one day. It is inspirational to me not just for the great knitting patterns but also to realize that yes, there are huge yarn companies like Lion Brand and Bernat (and nothing against them, their yarn choices over the years have gone from plain acrylics to some wonderful textures and blends), but small is possible. And small is beautiful and can be very successful. The book showcases 28 companies across the United States that make yarn- some hand dye, some are the farms growing the fiber, many have mini-mills they work with, and some are the mills themselves. The book is arranged by region (Northeast, South, Midwest, West) and highlights a few individual sellers from each region. The biggest sections are the Northeast and the West, which, knowing the history of the American textile industry, make perfect sense. The Northeast was home to the US textile industry during the Industrial Revolution, and the West has lots of acreage with lots of sheep (although I’m pretty sure cattle outnumber sheep in Wyoming). At the end of each region's section is also a list of other sellers.  The individual sellers provide a story of their who-what-when-where –why and there is a knitting pattern featuring the company’s yarn after each story. Each story also has pictures of the proprietors at work- working with their flocks, their tools of the trade, and finished yarns. I love the picture of handdyed yarns strung between trees from Farmhouse Yarns in page 19. Remember above when I said it was also inspirational to me- that’s one of those pics and is the one on page 129 of handdyed yarns on laundry drying racks at Red Barn Yarn. There’s a picture of Pagewood Farm’s outdoor dye area on page 151- I would love to have that someday. If you’re getting the book for the knitting patterns there are a 28 to choose from- small projects like mittens and hats, to large projects like car coats and shawls. My favorite patterns are the Cabled Car Coat on page 20, the Oquirrh Mountain Wrap on page 160, and Evergreen Ankle Socks on page 136. I like knitting socks (portable project), long length sweaters, and shawls, so it’s no doubt those three made the top want-to-knit. I think all the patterns are beautiful, but I will focus on those three possibilities right now (along with about 10 other knitting projects.) My only qualm with the book is this book is titled “Knit Local” which #1- kind of sounds like the book should be about local yarn shops, not US yarn companies. And #2- semantics aside, some of the companies have limited yarn lines made in the USA. Some like Brown Sheep Company in Nebraska, Green Mountain Spinnery in Vermont, and the companies that are on farms are 100% American. A few companies have several yarn lines, but only one made in the USA. I would have liked it to be a 100% yarns made in America book. It’s not like the author didn’t have many other choices- remember the lists of other businesses at the end of each region.

Still, hearing the stories of the farms and small cottage industries created by fiber-loving folks gives me a pick me up when I need it. Being a yarnie full time is possible with some skill, time, and gumption. I have the people in this book to prove it. Yes, it does. Cotton can come in a rainbow of muted natural colors including shades of tan, green, brown, and russet. Cotton, like sheep wool, was bred to be white for the same reason as wool- to be able to reliably dye the fiber a rainbow of colors in textile production. It is also bred to be long stapled. Cottons such as Pima and Acala have long fiber lengths of around 1 ½- 2 inches. Natural color cotton fiber length is shorter than it’s commercially bred cousins. The darker the natural color, the shorter the fiber length. Where Pima and Acala are shiny and slick, colorgrown cottons are incredibly soft and billowy and range from medium to matte shine. It does not fade. With repeated washings in hot water, the color deepens. So how is it to spin? If you asked me today I would say an utter pain. I haven’t spun cotton in awhile so I’m not used to the short draw I have to use to spin it. I also have to keep my hands closer to the orifice (the round part the yarn goes through to the bobbin). After a skein or two, I’m fine. Cotton takes practice. If you’re a beginning cotton spinner, it will take time to get the hang of it- it’s a completely different feel and technique than wool. Colorgrown cotton roving is a good place to start because the fiber is fluffy and sticks together better than slick Pima. Start with a lighter color such as tan or khaki. The red brown has really short staple length, so much that I won’t spin that color anymore. My only regular qualm about spinning cotton is the lint gets everywhere. The fibers get stuck on my hands, clothes, whatever furniture is near the carpet. Be prepared not to touch your nose when you're sneezing, otherwise cotton lint will get in your nose. Below is a sampling of my handspun colorgrown cottons yarns. |

AuthorYarn artisan, Spinning Gypsy, lover of all sorts of textile arts Archives

September 2014

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed